Liver Involvement in Systemic Primary (AL) Amyloidosis – Prevalence, Clinical Insights, and Implications

Table of Contents

Introduction

Systemic primary amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis) is an uncommon, multisystem disease resulting from misfolded immunoglobulin light chains that form insoluble amyloid fibrils. These fibrils deposit in multiple organs and interfere with normal function. Of involved organs, the liver is affected in 60–90% of patients, so hepatic amyloidosis is an important component of clinical evaluation.

Although it is commonly engaged, liver dysfunction in AL amyloidosis is too often underdiagnosed because symptoms are not specific, and routine liver function tests may be inappropriately bland early in the illness. Accurate appreciation of prevalence, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and management strategies is paramount to enhancing outcomes in patients.

Epidemiology of Hepatic Involvement

Prevalence

- 60–90% of patients with systemic AL amyloidosis have liver involvement.

- Most have subclinical hepatic infiltration, identified on imaging or biopsy but not clinically apparent.

- Hepatic disease can be present in conjunction with cardiac, renal, and gastrointestinal amyloid deposition, leading to multi-organ failure.

Risk Factors

- Increased age: Patients are most often in their 50s–70s.

- Male predominance: Slightly increased frequency in males.

- Plasma cell dyscrasia underlying: AL amyloidosis is caused by monoclonal plasma cell disorders secreting pathogenic light chains.

Pathophysiology of Hepatic Amyloidosis

Amyloid deposition within the liver involves primarily:

- Hepatic sinusoids – amyloid fibrils deposit in space of Disse.

- Portal tracts – enlargement by amyloid can compress hepatocytes and biliary channels.

- Vascular walls – deposition can compromise blood flow and hepatic perfusion. ### Mechanisms of Organ Dysfunction ##### Hepatocyte compression → mild cholestasis and hepatomegaly. ##### Vascular compromise → heightened portal pressures and ascites in advanced disease. ##### Interaction with other organ involvement → hepatic insufficiency can worsen renal and cardiac consequences. ## Clinical Manifestations

Hepatic amyloidosis often presents insidiously, with nonspecific symptoms:

- Hepatomegaly: Most common sign; often painless.

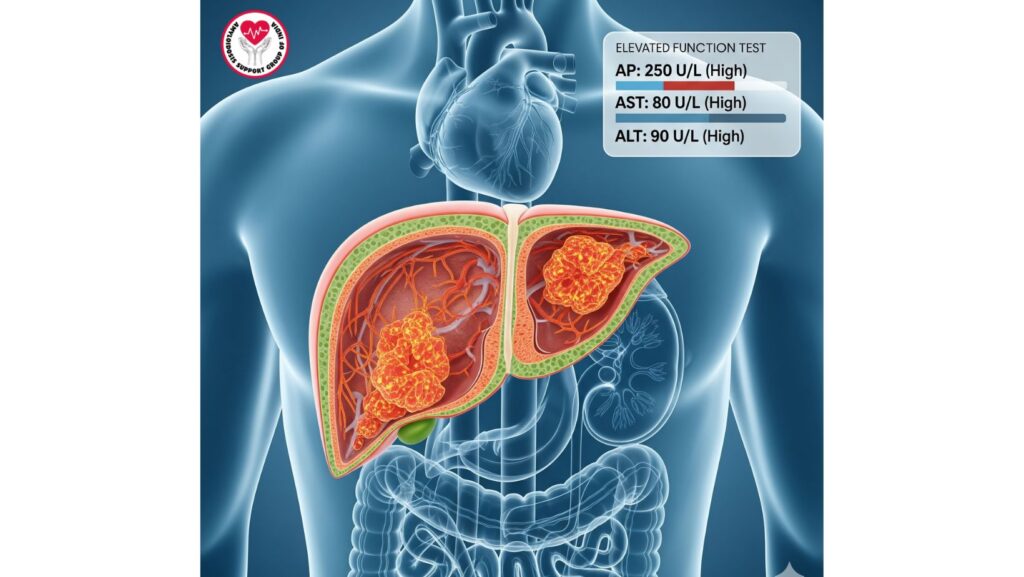

- Mild cholestatic liver function test abnormalities: Elevated alkaline phosphatase (AP), mild AST/ALT elevations.

- Jaundice: Rare, usually in advanced infiltration.

- Ascites: Occurs with portal hypertension or hypoalbuminemia.

- Fatigue and anorexia: Non-specific constitutional symptoms.

Laboratory Findings

- Alkaline phosphatase elevation is the most common abnormality.

- Elevation of bilirubin is rare early but reflects severe hepatic infiltration.

- Hypoalbuminemia can be due to concomitant nephrotic-range proteinuria or liver synthetic dysfunction.

Imaging Findings

- Ultrasound: Hepatomegaly with inhomogeneous echotexture.

- CT Scan: Nodular appearance of the liver, ascites; no hepatosplenomegaly in some cases.

- MRI: Useful for detecting infiltrative patterns and distinguishing amyloid from fatty liver disease.

Diagnosis of Hepatic Amyloidosis

Non-Invasive Approaches

- Serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP/UPEP) – detect monoclonal light chains.

- Serum free light chain assay – quantifies amyloidogenic proteins.

- Imaging studies – identify hepatomegaly, nodularity, or portal hypertension.

Liver Biopsy

- S Gold standard for diagnosis.

- Congo red staining is apple-green birefringent under polarized light. – Mass spectrometry can confirm AL type and differentiate from AA or ATTR amyloidosis. # Safety Precautions

- In patients with coagulopathy, ascites, or portal hypertension, transjugular liver biopsy is preferred.

- Percutaneous biopsy is avoided in high-risk patients to minimize the risk of bleeding. ## Prognostic Implications

- Hepatic involvement only seldom leads to death, but with cardiac or renal amyloidosis, the prognosis is much worse.

- Increased bilirubin, vast hepatomegaly, or portal hypertension are indicators of bad prognosis.

- MELD score may help estimate hepatic reserve in severe disease.

Multi-Organ Interaction

- Renal amyloidosis: nephrotic syndrome and hypoalbuminemia can worsen ascites.

- Cardiac amyloidosis: hepatic congestion may worsen heart failure symptoms.

- Systemic burden: Patients with extensive amyloid deposition are often poor candidates for transplantation.

Treatment Strategies

Medical Management

- Plasma cell-directed therapy: Bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, or daratumumab to reduce amyloidogenic light chains.

- Supportive care:

- Diuretics for ascites

- Nutritional support

- Surveillance for portal hypertension complications

Advanced Therapies

- Liver transplantation: Used in solitary hepatic amyloidosis but not in systemic AL amyloidosis because of the multi-organ involvement.

- Combination therapy: In individualized cases, liver and other organ transplantation combined may be considered in clinical centers.

New Therapies

- Amyloid fibril stabilizers – under research.

- RNA-silencing therapies – only in hereditary forms but could shed light on AL amyloidosis.

- Monoclonal antibodies against amyloid deposits – in clinical trials.

Case Examples from Literature

- Patient with massive hepatomegaly and raised AP – received bortezomib-based treatment, partial biochemical improvement, no transplantation owing to renal involvement.

- AL amyloidosis with jaundice and ascites – transjugular liver biopsy established amyloidosis; expired within weeks in spite of supportive treatment, emphasizing virulent hepatic infiltration.

- Isolated hepatic amyloidosis – extremely uncommon, successfully managed with liver transplant, demonstrating that very careful selection of patients is important.

Clinical Pearls

- Early detection of hepatic involvement is essential for treatment and prognosis.

- Imaging and non-invasive labs are handy screening modalities, but biopsy is still definitive.

- Multidisciplinary management (cardiology, nephrology, hematology, hepatology) enhances outcomes.

- Supportive management is vital in advanced hepatic amyloidosis to ensure quality of life.

Future Directions

- New therapeutic strategies against amyloid fibrils may enhance hepatic outcomes.

- Development of biomarkers to identify early hepatic involvement and predict prognosis.

- Palliative care integration for systemically diseased patients with multi-organ involvement to maximize quality of life.

- Enlarged clinical trials to better define transplantation criteria for isolated hepatic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

Hepatic involvement is prevalent in systemic primary (AL) amyloidosis and occurs in 60–90% of patients and is a major contributor to disease morbidity. Although exceedingly uncommon as the sole cause of death, liver infiltration co-mingles with cardiac and renal dysfunction, making management and prognosis more difficult.

Key takeaways:

- Have high suspicion for hepatic involvement in AL amyloidosis.

- Employ biopsy and mass spectrometry for final diagnosis.

- Supportive and plasma cell-directed therapy is still at the heart of treatment.

- Novel treatments such as transplantation are now used with appropriate patient selection because of systemic disease.

Awareness of hepatic involvement is critical to early diagnosis, multidisciplinary management, and maximizing outcomes in patients with systemic AL amyloidosis.