In some respects, amyloidosis is often difficult to recognize. Its symptoms are vague and nonspecific, often mimicking those of more common conditions. For instance, shortness of breath can be an indicator of heart disease associated with much more common medical problems such as hypertension, heart failure or lung disease. Another example is protein in the urine (“proteinuria”), which can occur in amyloid-related kidney injury. Because much more common diseases like diabetes can also cause protein in the urine, health care providers do not normally think of amyloidosis first. Amyloidosis typically appears in middle-age and older individuals, but it can also occur during one’s 30s or 40s, and occasionally even younger.

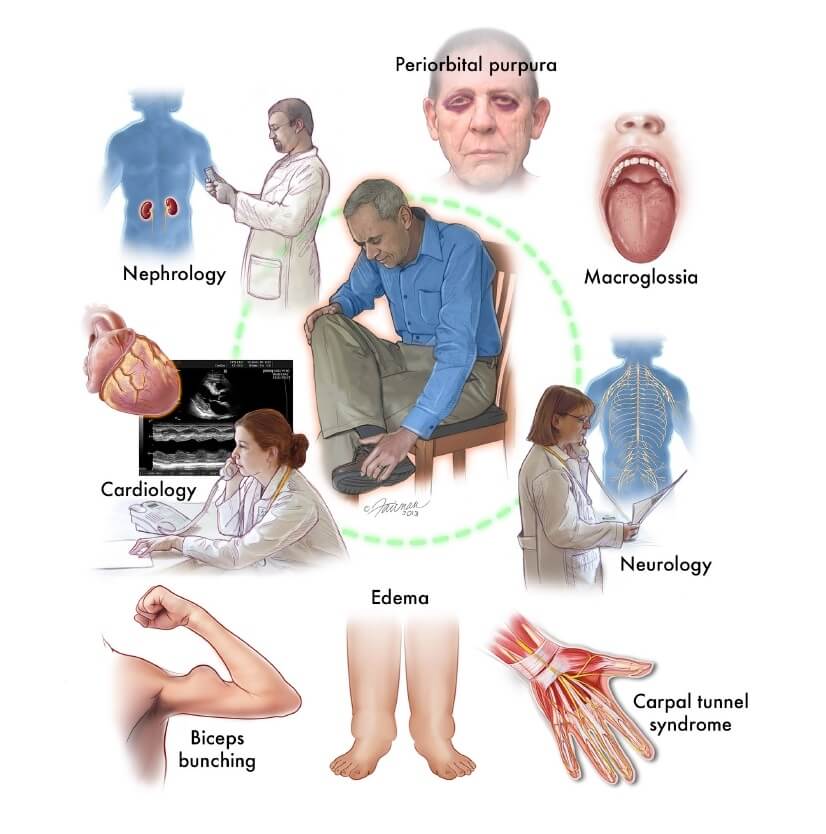

Depending on where in the body they occur, amyloid deposits can cause weight loss, fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness upon standing, swelling in the ankles and legs, numbness and tingling in the hands and feet, foamy urine, alternating bouts of constipation and diarrhea, and feeling full quickly after eating. Carpal tunnel syndrome can often be seen with AL and ATTR amyloidosis patients, and lumbar spinal stenosis can be frequent with ATTR patients as well. Also, if a patient bruises easily, especially around the eyes (periorbital purpura), or has an enlarged tongue (macroglossia), AL amyloidosis is very likely the underlying cause. Even as a tell-tale group of symptoms persists and worsens, many physicians do not consider (or remember) an uncommon, insidious disease such as amyloidosis.

It is not unusual for an affected individual to see several physicians over a period of many months or even years before a biopsy (tissue sample) is taken. Some patients develop organ failure before a proper diagnosis is made. When a biopsy is performed, it is extremely important that the pathologist is informed of the suspected diagnosis to ensure appropriate testing of the sample (see next section). Without the clinical information, the pathologist may only consider more common diagnoses and miss amyloidosis. While amyloidosis can affect just a single organ, it often causes systemic problems (i.e., it affects more than one organ system). The organs most often involved in AL amyloidosis are the kidneys (about 70% of patients), heart (60%), nervous system (30%), and gastrointestinal tract (10%). Therefore, the combination of kidney, heart, nerve, gastrointestinal and/or liver disease – with no other obvious cause – should prompt physicians to test for amyloidosis.

The four most common clinical settings in which amyloidosis should be considered are:

- Loss of massive amounts of protein in the urine (proteinuria; also called nephrotic syndrome) This suggests kidney involvement.

- Stiff or thickened heart (restrictive cardiomyopathy) as seen on echocardiogram; low voltage seen on electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG); irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) that is resistant to conventional treatment, often associated with normal or low blood pressure; or unexplained heart failure. These findings suggest heart involvement.

- Enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) without alcohol consumption or other explanation, often with abnormal liver blood tests, including elevated alkaline phosphatase. This suggests liver involvement.

- Numbness, tingling, or pain in the fingers or toes (peripheral neuropathy), carpal tunnel syndrome (especially when affecting both hands), or alternating bouts of constipation and diarrhea with or without feeling lightheaded due to a drop in the blood pressure when standing up (autonomic neuropathy). These symptoms could suggest nerve involvement.

Testing for Amyloidosis

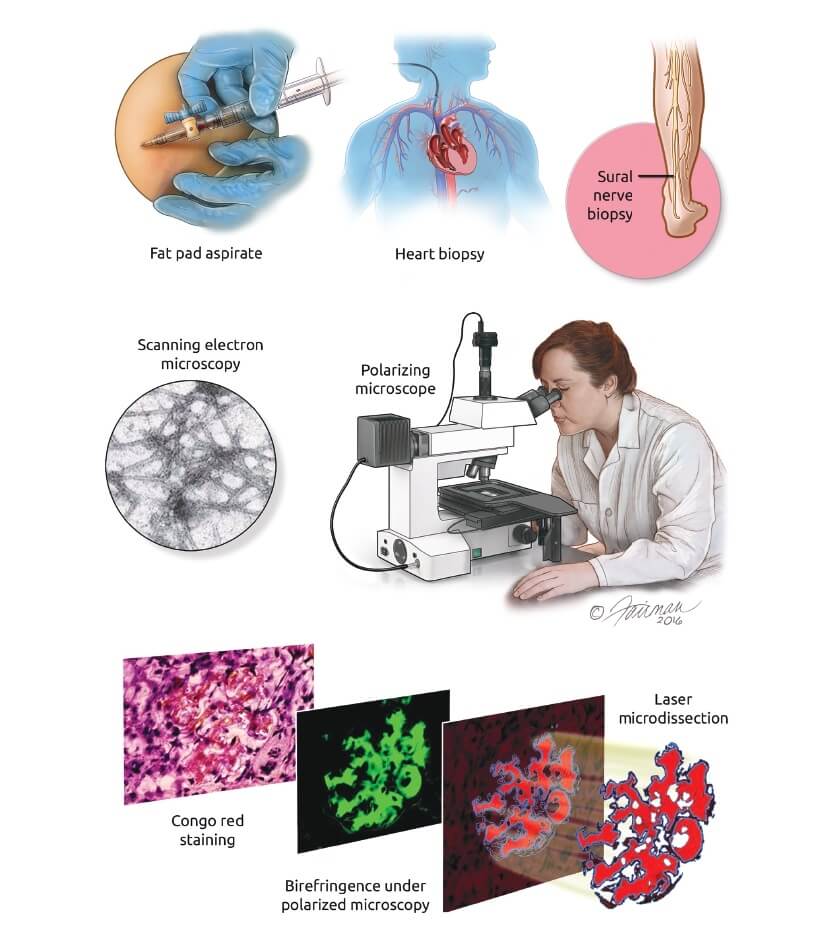

Once amyloidosis is suspected, it can sometimes be identified, if present, with a very simple office procedure. Early detection and accurate evaluation are essential for patients to benefit from the many therapies now available. Blood and urine tests may provide hints about the diagnosis, but the gold standard for detecting amyloid deposits is to perform Congo red staining on a tissue sample. While biopsies can be taken from the gums, nerves, kidney, liver, tongue, heart, rectum, or other organs, the easiest way to get a tissue sample is to aspirate fat from the abdomen. In this minimally invasive procedure, the skin of the belly is numbed with a local anesthetic, and a needle is used to perform a mini liposuction of fat from under the skin. The sample obtained is usually about the size of a chickpea or a pencil eraser. Because of the common misfolded structure of all amyloid, it has a pink color when dyed with Congo red stain and viewed under a standard microscope, and a characteristic applegreen appearance when viewed with a polarizing microscope.

This signature technique can diagnose amyloidosis in 70-80% of patients with AL amyloidosis, but only about 15-20% of patients with ATTR amyloidosis. A negative fat aspirate does not rule out amyloidosis. In the case of AL amyloidosis, a fat pad aspirate and bone marrow biopsy are two of the initial tests performed. If the fat pad aspirate and bone marrow biopsy are negative for amyloidosis, but suspicion of the disease remains high, a direct biopsy of the involved organ (e.g., the heart, kidney, or liver) should be done. If amyloid is present in the biopsied tissue, Congo red staining will yield a definitive diagnosis in nearly 100% of cases. It is important that the pathologist working on the biopsy has experience with Congo red staining, as over-staining the tissue sample may give false results. Visualizing the tissue with an electron microscope will show the classic structure of amyloid fibrils and is helpful in confirming its presence.

Welcome to Amyloidosis Support, Which are under Ram Dayalu Singh Sustainable Development Foundation (RDSSDF), a beacon of hope and progress for the sustainable development of India. As a National Level Public Charitable Trust, it is dedicated to providing comprehensive support and innovative solutions.

Welcome to Amyloidosis Support, Which are under Ram Dayalu Singh Sustainable Development Foundation (RDSSDF), a beacon of hope and progress for the sustainable development of India. As a National Level Public Charitable Trust, it is dedicated to providing comprehensive support and innovative solutions.