Proving that amyloid is present in an organ is only the beginning of the process. Next it must be determined what kind of amyloid is causing the disease to plan for an appropriate, individualized treatment. In all cases, identifying the amyloid type must be based on evaluation of the abnormal protein deposits in the affected tissues. It is recommended that this additional testing on the tissue sample be performed at a specialized amyloidosis center with sophisticated diagnostic tools at their disposal. Consultation with experts at such a center should also be considered if, after extensive local testing, a diagnosis of amyloidosis remains suspected but not established.

Proving that amyloid is present in an organ is only the beginning of the process. Next it must be determined what kind of amyloid is causing the disease to plan for an appropriate, individualized treatment. In all cases, identifying the amyloid type must be based on evaluation of the abnormal protein deposits in the affected tissues. It is recommended that this additional testing on the tissue sample be performed at a specialized amyloidosis center with sophisticated diagnostic tools at their disposal. Consultation with experts at such a center should also be considered if, after extensive local testing, a diagnosis of amyloidosis remains suspected but not established.

A simple blood test to measure the levels of kappa and lambda serum free light chains when coupled with measures for monoclonal proteins in the serum and urine (serum and urine electrophoresis with immunofixation) will show disproportionately elevated levels of one type or the other in roughly 98% of patients with AL amyloidosis. This test is often one of the earliest ones done. A bone marrow biopsy, as mentioned above, often reveals amyloid deposits and in almost all cases, the abnormal (clonal) plasma cells which produce the defective, amyloid-forming light chains. These cells are identified using special staining (immunohistochemistry) or cell sorting techniques (flow cytometry), if these tests are negative, other forms of the disease should be investigated including the ATTR types.

Molecular and genetic testing can be performed on blood samples to see if the patient has any of the hereditary types of amyloid (e.g., TTR, fibrinogen, lysozyme, apolipoproteins AI and AII, and gelsolin). If one has such a mutation, then his or her children each have a 50% chance of inheriting it. It should be emphasized that the presence of a genetic mutation does not guarantee a person will develop amyloidosis. Also, it is possible, albeit rare, to develop non-inherited types of amyloidosis (like AL or AA) even when you are a carrier of a mutation or genetic variant associated with inherited amyloidosis, or even to develop two types of amyloidosis at the same time. The complicated detective work needed to sort out these types of cases often requires the clinical expertise and advanced diagnostic testing only available at major amyloidosis centers. Understandably some people are reluctant to be tested for a genetic disease.

In the United States, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), legislates that patients who have a hereditary predisposition for diseases, such as amyloidosis, cannot be discriminated against with respect to employment or health insurance. Patients are encouraged to meet with a licensed genetic counselor before testing. Importantly, sometimes a patient’s other medical history provides clues about the most likely type of amyloidosis. For patients with chronic inflammatory or infectious conditions, or long-term kidney dialysis, primary consideration would be AA or Aβ2M amyloidosis, respectively. Recurrent strokes or progressive dementia with evidence of recurrent small brain bleeds on an MRI suggest cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). In a person over the age of 50, presenting with congestive heart failure with an increased wall thickness on echocardiogram in the absence of hypertension, a primary consideration would be wild type ATTR amyloidosis (ATTRwt).

Meanwhile, recent advances in the field of proteomics promise to revolutionize the precise diagnosis of amyloidosis. Proteomics involves the study of the entire collection of proteins in an organism or environment. Unlike standard immunochemistry techniques, which in many cases fail to accurately diagnose which precursor protein is responsible for the amyloid deposits, proteomics can identify the specific protein in the amyloid deposits with or without genetic mutations. Laser microdissection followed by mass spectrometry (LDM-MS) is the premier technique in typing amyloidosis.

To perform the test, Congo red positive samples are dissected and broken down into smaller components of protein molecules (called peptides). The peptides are then analyzed using a process known as “liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry,” also termed mass spectrometry or LMD-MS, for short. Studies have shown that LMD-MS has the capability to identify most known amyloid proteins with virtually 100% accuracy, as well as the ability to characterize new ones. Certain forms of amyloidosis which have historically been underdiagnosed, such as the Val122Ile, the TTR variant that causes cardiac amyloidosis in Black Americans, and the wild type ALECT2 protein that causes kidney disease in patients of Mexican heritage, are readily identified using LMD-MS.

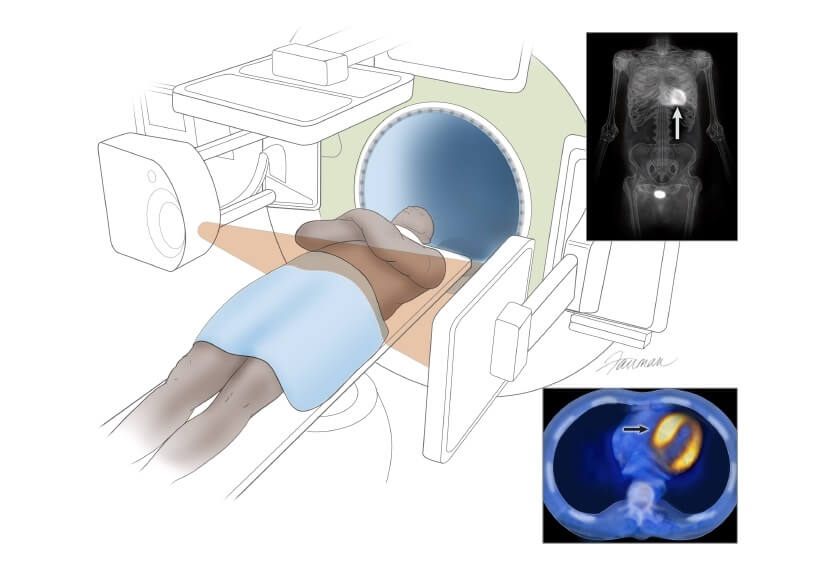

There is one circumstance in which cardiac amyloidosis may be diagnosed without a biopsy. If ATTR cardiac amyloidosis is suspected, a diagnosis can be made using a nuclear medicine scan, Tc-99m PYP (pyrophosphate scan) in the United States, DPD/HMDP in Europe. If there is abnormal tracer uptake in the heart along with typical echocardiographic or cardiac MRI findings, and if screening blood and urine tests for AL are negative, the diagnosis of ATTR can be confirmed. It should be noted that other types of amyloidosis such as AL or apolipoprotein can occasionally result in a positive nuclear medicine scan, as can other technical issues, such as blood pool. The diagnosis of amyloidosis based on cardiac imaging alone requires considerable expertise and should involve cardiologists and/or nuclear medicine specialists with experience evaluating amyloidosis.

In summary, diagnosis of a specific type of amyloidosis requires the evaluation of clinical factors such as age, ethnicity, family history, personal medical history, together with sophisticated diagnostic testing.

Welcome to Amyloidosis Support, Which are under Ram Dayalu Singh Sustainable Development Foundation (RDSSDF), a beacon of hope and progress for the sustainable development of India. As a National Level Public Charitable Trust, it is dedicated to providing comprehensive support and innovative solutions.

Welcome to Amyloidosis Support, Which are under Ram Dayalu Singh Sustainable Development Foundation (RDSSDF), a beacon of hope and progress for the sustainable development of India. As a National Level Public Charitable Trust, it is dedicated to providing comprehensive support and innovative solutions.