Unexplained Liver Failure: Taking AL Amyloidosis as a Possible Cause into Account

Table of Contents

Introduction

Unexplained liver failure is a challenging diagnostic problem in clinical practice. Although routine consideration is given to common causes such as viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and drug-induced liver injury, unusual etiologies such as systemic primary (AL) amyloidosis can be missed.

AL amyloidosis is a condition defined by misfolded immunoglobulin light chains deposited as amyloid fibrils in various organs, including the liver. Liver involvement may vary from subclinical abnormalities to severe cholestatic liver failure, which, although rare, is universally fatal.

This complete manual covers:

- Epidemiology and prevalence of hepatic AL amyloidosis

- Clinical presentation of patients with liver failure

- Laboratory and imaging features

- Diagnostic strategies

- Prognosis and survival comparisons

- Management approaches and therapeutic dilemmas

- Clinical tips and future directions

Epidemiology of Hepatic AL Amyloidosis

Prevalence and Importance

- 60–90% of systemic AL amyloidosis patients have some level of liver involvement.

- Clinically significant liver failure is uncommon (<10%) but carries a poor prognosis.

- Prompt recognition is important to distinguish from other etiologies of liver impairment.

Demographics and Risk Factors

- Generally involves older adults, typically in the 55–70 years age range.

- Male dominance seen in certain studies.

- Risk indicators for bad liver disease are:

- Heavy amyloidogenic light chain load

- Accelerated progression of amyloidosis

- Involvement of multiple organs, especially heart and kidneys

Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of Liver Dysfunction in AL Amyloidosis

- Sinusoidal deposition: Compresses hepatocytes, impairing function.

- Portal tract infiltration: Causes cholestasis and bile duct obstruction.

- Vascular compromise: Reduces hepatic perfusion, worsening hepatocyte injury.

- Systemic effects involving multiple organs: Potentiates metabolic derangement and risk of therapy toxicity.

Clinical Consequences

- Cholestasis: Causes jaundice, pruritus, and hyperbilirubinemia.

- Synthetic dysfunction: Hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and ascites.

- Metabolic complications: Metabolically impaired clearance of drugs metabolized by the liver.

Clinical Presentation

Hepatic Involvement Symptoms

- Jaundice: Very early sign of fulminant liver involvement.

- Hepatomegaly: Can be tender or non-tender.

- Pruritus: Cholestatic in origin.

- Ascites: Due to hypoalbuminemia and portal hypertension.

- Fatigue, anorexia, malaise: Frequent systemic manifestations.

Patients Without Liver Failure

- Usually asymptomatic, found incidentally.

- Mild elevations in LFTs (AP, AST/ALT).

- Synthetic function preserved.

- Prognosis more related to cardiac or renal involvement than liver disease.

Laboratory Evaluation

Liver Function Tests

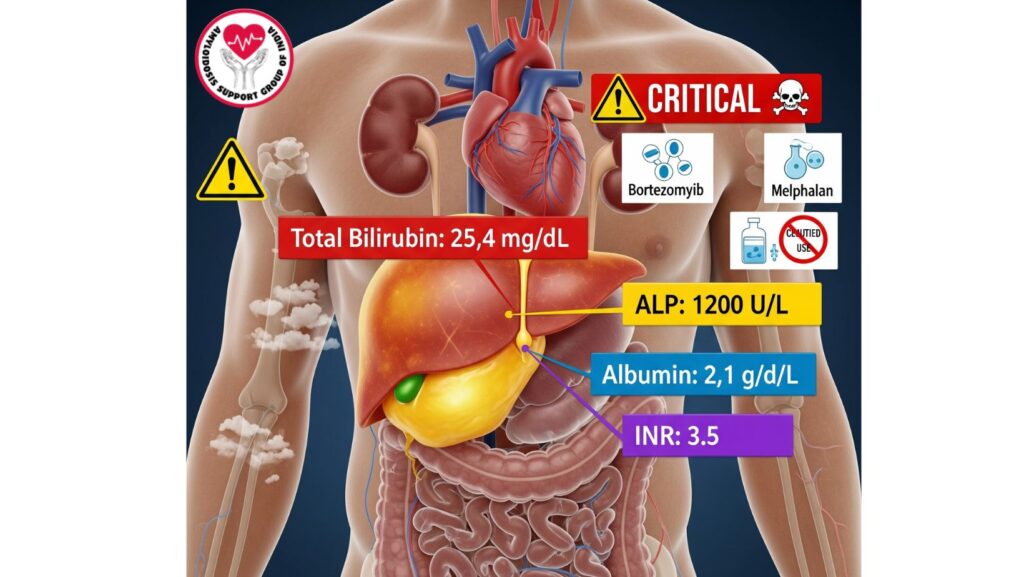

- AST/ALT: Mild to moderate elevation.

- Alkaline phosphatase (AP): Often >1,000 IU/L in severe cases.

- Total bilirubin: Significantly elevated in liver failure (>10 mg/dL).

- Albumin: Reduced because of compromised synthesis or nephrotic syndrome.

- INR: Elevated, reflecting synthetic dysfunction.

Additional Laboratory Tests

- Serum and urine protein electrophoresis (SPEP/UPEP)

- Serum free light chain assay

- Viral hepatitis panels, autoimmune markers, and ferritin to exclude common etiologies

Imaging Modalities

Ultrasound

- Reveals hepatomegaly and echotexture abnormalities.

- Shows ascites and splenomegaly.

CT and MRI

- Assesses nodular liver appearance and portal hypertension.

- Detects secondary complications like varices or ascites.

MRI Elastography

- Determines liver stiffness and distinguishes fibrosis from amyloid deposition.

Liver Biopsy

Indications

- Diagnoses in unexplained liver failure.

- Needed when noninvasive testing is inconclusive.

Techniques

- Percutaneous biopsy: Routine, but dangerous with coagulopathy or ascites.

- Transjugular biopsy: Best in patients with risk of bleeding.

Histopathology

- Congo red staining: Diagnoses amyloid deposition (apple-green birefringence under polarized light).

- Mass spectrometry: Detects AL-type amyloid fibrils.

- Lack of inflammation or fibrosis characterizes amyloidosis from other liver disorders.

Differential Diagnosis

- Viral hepatitis (A, B, C, E)

- Drug-induced liver injury

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Primary biliary cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

- Infiltrative diseases: sarcoidosis, metastatic cancer

AL amyloidosis must be ruled out in patients presenting with unexplained liver failure, particularly if there is: - Multi-organ involvement

- Nephrotic-range proteinuria

- Cardiac failure

Prognosis

Patients With Liver Failure (Jaundice)

- Median survival: ~3 months

- Sudden progression to hepatic synthetic failure

- Often linked with multi-organ amyloidosis

Patients Without Jaundice

- Median survival: ~2 years

- Often subclinical involvement of liver

- Prognosis determined by cardiac and renal disease

Survival Comparison

| Feature | With Jaundice | Without Jaundice |

| ———————– | —————– | ———————- |

| Median Survival | ~3 months | ~2 years |

| Bilirubin | Highly elevated | Mild/slightly elevated |

| AP | >1,000 IU/L | Mild elevation |

| Synthetic Function | Impaired | Preserved |

| Multi-Organ Involvement | Common | Less frequent |

Treatment Challenges

Limitations Secondary to Liver Failure

- Bortezomib and melphalan: Liver metabolism; enhanced toxicity in hepatic failure

- Cyclophosphamide: Dose reduction required

- Daratumumab: Relatively safer but caution should be exercised

- Severe liver impairment frequently excludes conventional chemotherapy

Supportive Care

- Nutritional support for hypoalbuminemia

- Diuretics and paracentesis for ascites

- Pruritus management

- Early incorporation of palliative care because of the fast progression of the disease

Liver Transplantation

- Infrequently possible; largely contraindicated in multi-organ involvement

- Only considered in isolated hepatic amyloidosis

Case Studies

- Patient A: Hyperacute jaundice, ascites, coagulopathy; biopsy established AL amyloidosis; survival 4 weeks after presentation.

- Patient B: Multisystem involvement with end-stage cholestatic liver failure; palliative management; survival 3 months.

- Patient C: Isolated hepatic amyloidosis; transplant of the liver undertaken; survival >2 years.

Clinical Pearls

- Always keep in mind AL amyloidosis in unexplained liver failure.

- Jaundice suggests high-risk, poor-prognosis liver disease.

- Improved diagnosis and supportive treatment enhance planning for management.

- Multi-organ impairment determines therapeutic options and prognosis.

- Palliative care is essential in advanced cholestatic liver disease.

Future Directions

- Creation of hepatic-sparing therapies for AL amyloidosis

- Biomarkers for early detection of high-risk hepatic involvement

- Clinical trials for safe regimens in patients with liver failure

- Advanced imaging for monitoring hepatic amyloid burden

Conclusion

Unexplained liver failure is a diagnostic dilemma that must encompass AL amyloidosis as a cause. Important points:

- Extensive liver involvement in AL amyloidosis is uncommon but always fatal.

- Early detection, diagnosis, and multidisciplinary management are crucial.

- Therapeutic choices are limited by altered hepatic metabolism, necessitating careful planning.

- Supportive and palliative care continue to be the hallmark of patient-centered management.

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion of AL amyloidosis in patients with unexplained liver failure, especially with multi-organ dysfunction, nephrotic syndrome, or cardiac impairment. Early treatment maximizes quality of life, therapeutic safety, and patient outcomes.